In my Digital Art Processes class, we were given the assignment to make a set of postage stamp designs centering around a particular theme or idea. Because of my interests in ecology and pedagogy, I decided to create a conceptual interactive project that would involve the exchange of knowledge and resources between theoretical participants and the natural environment. I created the stamps below to demonstrate what these theoretical participant-made stamps could look like.

Sage grouse and their relatives are threatened species native to North America which depend upon sagebrush for their main source of food and nesting shelter. Their numbers are declining due to habitat destruction.

Pygmy rabbits are another endangered species native to North America which rely on sagebrush for food and shelter. One subspecies or genetic line, the Colombia Basin pygmy rabbit, is already extinct.

Big sagebrush and its relatives, which are primarily threatened by human-caused habitat destruction, are ecologically connected to a multitude of animal species. This stamp and the two previous could be made of fibers taken from cheatgrass, which is the invasive plant species that has taken over the biggest amount of sagebrush habitat. These stamps would also be embedded with sagebrush seeds.

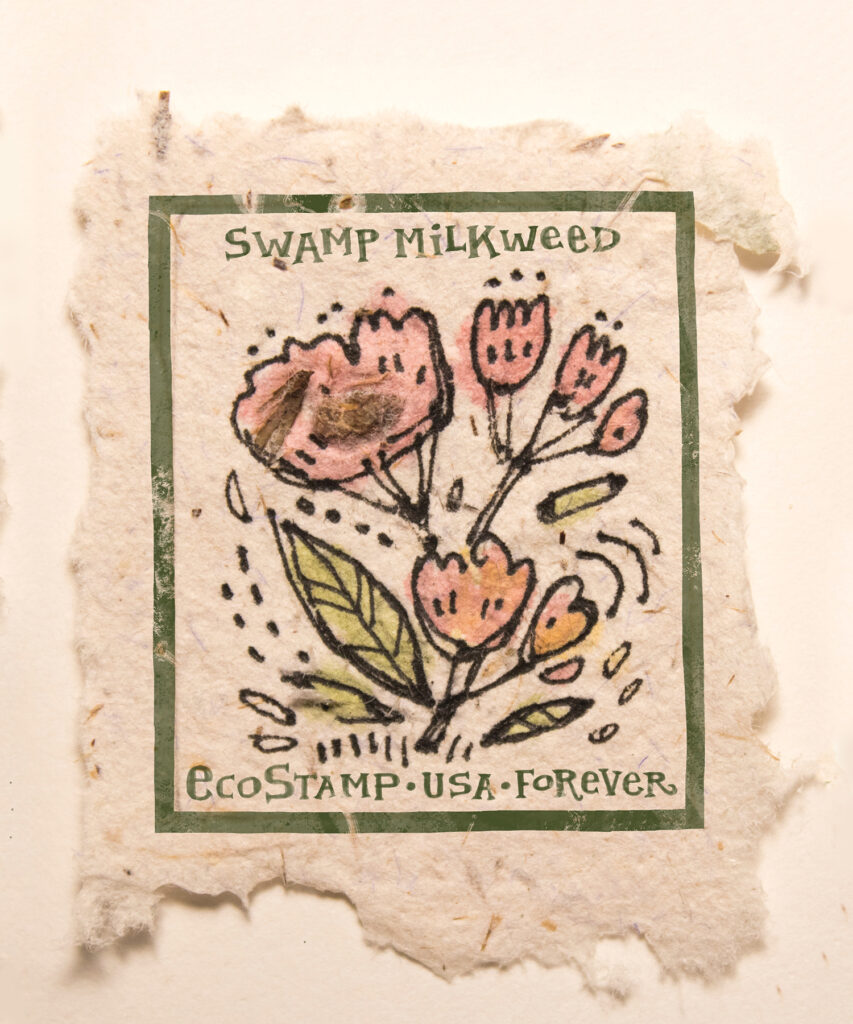

Monarch butterflies, native to the Americas, are endangered due to habitat loss and climate change. Their reproductive survival depends upon access to certain types of milkweed plants.

Swamp milkweed is one of the important plants used by monarch butterflies and other animal species for food. Many types of milkweed are threatened due to habitat destruction. The paper of this stamp and the one above could be made from kudzu, which are an invasive plant which commonly outcompete milkweed and other native plants. These stamps would also contain milkweed seeds.

Watch the video below for information about the project.

Below is a longer explanation detailing how my concept would work.

The “EcoStamps” project (perhaps sponsored through a partnership between the USPS and the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, or other institutions interested in protecting the environment) would move through three phases:

Phase One: Preparation

- Community members with skills/knowledge in environmental science, the arts, and education would be invited to participate in this phase of the project.

- These participants would collaborate to create an easily accessible online platform which would be a compilation of educational materials about papermaking, stamp production, and ecology. It would also feature an open-source database containing lists of and links to information about threatened animal species, the native plants they depend upon, and invasive plant species which compete with those native plants for resources. It would have interactive maps which show the locations of all these species and their bioregions. All of these materials would be available in different languages to promote accessibility.

Phase Two: Action

- People would be invited to participate in the making, sharing, and eventual planting of “EcoStamps.” These people could be interested individuals, families, and friend groups, as well as more formally organized groups situated in schools, libraries, museums, community gardens, volunteer groups, clubs, community centers, and any other organization.

- People would first access the online platform to learn about plant and animal species in their region. Then they would go outdoors to find and document the native and invasive species growing in their communities. They would gather seeds from native plants, along with fibers from invasive plants (stems, leaves, roots, etc). They would enter their findings into the online database.

- On the website, participants would select the specific species that they are focusing on. A set of official rubber ink stamps would be mailed to them or be available for use at their local post office. These stamps would provide a standardized border for the postage stamps that participants will be creating in the next step. These rubber ink stamps would have a postage stamp outline, a species label, and a postage value. This way, all of the stamps would be verifiable as part of the EcoStamp project.

- Participants would begin the stamp-making process with help from tutorials available through the online platform. First, they would make paper out of the invasive plant fibers, with native plant seeds embedded in the paper. Then, using the official rubber ink stamps provided to them, they could easily outline and then cut the blank stamps out of the handmade paper.

- Participants could create their own stamp designs in a variety of ways: digitally (if their paper was thin enough to run through a printer), through their own small relief prints (for example, with a hand cut eraser stamp), or through drawing and/or painting directly on the stamp paper. They would be encouraged to illustrate the species featured on their stamp, but even if their designs are illegible or abstracted, the standardized stamp border would provide a legible species label.

- Then, the participants would be able to glue their seed-paper stamps onto envelopes and send them to other participants (along with letters, photos, gardening advice, etc). Participants would be matched to other participants through the online platform, either by algorithms or a system of filters, in order to ensure that seeds are sent to the right bioregion, preferably in places that need more of a certain plant species. For example: a community garden in Utah with plenty of swamp milkweed growing nearby could be matched to a school in Idaho which did not find any milkweed in their community. This way, some swamp milkweed seeds could spread to a new location, helping the threatened Monarch butterfly population along their migration route. In some cases, these pairings between participants could be mutually beneficial, allowing for one group with excess of a certain species to share with another group in need of that species, and vice versa. For example, maybe that school in Idaho had access to some big mountain sagebrush. They could send some seeds back to their friends in Utah, who could then plant the seeds and add some biodiversity to their community garden. This would provide more food and shelter for threatened species such as sage grouse, pygmy rabbits, and other wildlife in their area.

- After the mailed seeds arrived at their destination, they would be planted (and hopefully tended) in fields, vacant lots, forests, parks, backyards, gardens, or any other available location and thus reintroduced to the ecosystem.

Phase Three: Follow-Through

- Participants would be encouraged to document the growth of their plants, record any desired information about their learning experience, and track any sightings of the animals that rely on those plants. They could enter their documentations into the online database, so that anyone could see the development and spread of this project, learn from their process, and be inspired to join.

- Participants would also be encouraged to cultivate relationships with the people they exchanged seeds with. They could continue a penpal-style friendship: sharing advice, photos of any plants and animals linked to the project, and perhaps more seeds, as the plants complete more growth cycles. Hopefully, new networks of human-to-human relationships, collaborations, and communities could be an outcome of this project, in addition to the impact to natural ecosystems.